Welcome to Homemaker Oxford, research in motion by Transition by Design. We're interested in how empty and underused spaces could be used to help tackle extreme housing need in Oxford. This map is a perpetual pin-board of our research including what we've done, what we've learned, and what we think.

Move around on the map to find areas or topics that interest you and click through to find out more.

Legend

| Article | ||

| Audio | ||

| Video |

Find the Gap

Across Oxford there are hundreds of small, undeveloped sites of all shapes and sizes in well-connected locations which lie empty or underused. Travel anywhere in Oxford and you’ll spot these: garage sites, underused car parks, stalled development sites, spaces for which the potential becomes harder to ignore as the city’s housing crisis deepens and levels of homelessness rise.

Empty sites are most commonly found in estates, between terraced streets along major transport routes, or small infill plots between existing buildings, but can also appear as expanses of land in city centres where long term redevelopment plans have stalled. These sites are often overlooked, victims of delayed development processes, land banking, and a myriad of other real and significant blocks to development.

Throughout our research working with people experiencing homelessness or extreme housing need in Oxford we’ve explored in great detail the importance of where a house is located, and the connections it enables to people and place.

When Dave had a heart attack, it was the mechanic at the local garage who called the paramedics that saved Dave’s life because he’d not been in that morning to pick up their copy of the Daily Telegraph once they’d finished with it, as he did every morning. When Yaz felt ready to apply for her first job following a spell in prison, it was her neighbour who she called on at 9.30pm to give her application a final look-over before the 10pm deadline. Leaving the house was less-anxiety inducing for Sal when he lived in the last place because he knew enough of his neighbours that he could be confident of a helping hand to get his mobility aid onto the bus. When we opened a public living room in Little Clarendon Street, two of our regulars, who lived together in the same block of charity-provided supported living in Cowley, spent a quarter of their weekly cash on the bus fare to come and hang out together in our space because they had nowhere closer to home to relax together.

There is a growing consensus that building homes within existing communities and infrastructure is the most sustainable approach, both socially and environmentally. It’s an idea which Urbed proposed for Oxfordshire in 2014, as part of their Wolfson Prize winning proposal for a garden city approach to growth in the county. Building more densely - close to or within existing communities - can create more ‘liveable’ places, journeys are shorter, greenspaces are more mature and better used, more amenities are in close proximity, and there are pre-existing groups, regular activities and networks to join. Streets and neighbourhoods already have a rhythm for life to follow.

At a city-scale this approach also promotes connectivity, it can reduce the cost of development by reducing the need for expensive and carbon hungry new infrastructure, it utilises existing transport routes, promotes walking and cycling and reduces car dependency. The result is healthier, more sustainable, and more liveable towns and cities.

We’ve been actively exploring how to build new, low-carbon social homes within existing communities in Oxford for a while now and it’s hard. Really hard. It is therefore unsurprising that the majority of Oxford’s new social home building is happening on the periphery of the city (often on greenfield or even greenbelt land) in new developments such as Barton Park. Last year the Place Alliance drew our attention to what we can learn from the design of our homes and neighbourhoods through the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Their report does not fare well for developments like Barton Park in East Oxford. It found people living in flats were less comfortable than those in houses, that new-build estates were home to some of the least comfortable, and that the older the housing stock the greater the sense of community.

We know that taking a patchwork approach to developing new low-carbon social homes, using small urban development sites is more difficult than the current volume-led approach that is favoured by local and central governments. But we think it’s worth it because of the potential for providing wonderful homes that don’t break the carbon budget. Embracing Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) – those using modular and off-site factory-built processes - also makes this approach more possible than ever. And we’re not alone, there are some fantastic projects by some wonderfully pioneering folk for us to learn from.

We Can Make in Bristol has mapped and identified over a thousand micro and infill sites in the community of Knowle West and have been working to turn the community into developers by creating tools to open source the process. In 2017 they built a prototype home constructed from ecological materials including straw and timber, a demonstration of how these sites could be used. In Autumn 2021 they began on site to build their first two homes for local people in need of housing, using unused spaces at the bottom of existing gardens.

Walsall Housing Group in the Midlands is an example of a Registered Provider leading the charge. They have identified over 200 unused garage sites within their own housing stock, many of which were historically discounted for development due to access issues but are now being unlocked through the use of modular and off-site technologies.

Bromford Housing, another Registered provider in Gloucestershire has put its research into MMC into practice by securing planning permission for a compact terrace of 6 affordable homes adapted to the form and scale of the garage plots. The homes will be built in a factory by Totally Modular, incorporating the latest renewable energy technologies to minimise running costs and reduce their ecological impact.

Similar examples that explore temporary or ‘meanwhile’ approaches are also popping up, with varying degrees of success.

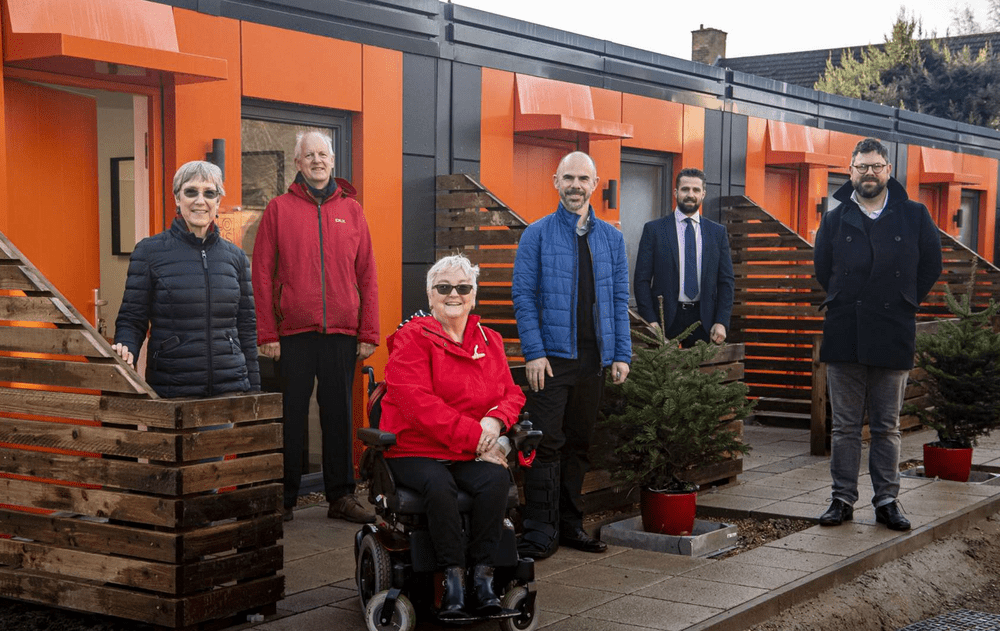

One promising example is by the Charity Jimmy’s Cambridge who in 2020 built 16 homes for individuals experiencing homelessness. They unlocked vacant land via an innovative partnership between landowners Cambridgeshire County Council and a local church. More homes are planned for 2021, to be custom-built and designed in such a way to be suitable for short- or medium-term sites that would otherwise remain vacant.

Gap House by design agency BDP’s Bristol-based team is a concept which has been developed as part of an Innovate UK funded research project. The proposals which have been showcased at the Bristol Housing Festival are designed to fit on vacant urban garage plots, to be built off-site and with affordability in mind. BDP have developed the proposals in partnership with an MMC zero carbon housebuilder.

Kenilworth Road House in Ealing by Crawford Partnership have demonstrated how you can transform a former garage into a beautiful home which tackles overlooking issues through the position of glazing and the creation of a front courtyard. The scheme addresses planning issues headon, offering a contemporary design that sits sensitively within its context, at a scale aligned with surrounding buildings.

Lewisham Borough Council have shown how local authorities can play a leading role through the creation of its Supplementary Planning Document on Small Sites which sets out a strategic vision for delivering more affordable zero carbon homes and an accompanying design guide for best practice

The Launchpad scheme in Bristol has taken an innovative approach by focusing on housing young adults impacted across the spectrum by unaffordable student and private rentals, as well as those trapped in supported living. The scheme uses MMC to create homes for 31 young people from diverse backgrounds including key workers, students and individuals who’ve experienced homelessness, underpinned by a partnership between a housing association, United Communities, a youth support charity, 1625i, and the University of Bristol Student Union.

The scheme aims to create an aspirational environment where young people can learn from each other, facilitated by a community development worker; access to University of Bristol facilities and direct housing support.

The London Community Land Trust is bringing forward a former garage site in Lewisham as part of a commitment by its Mayor to work with local people to deliver more housing in the area. Architects, Archio, were selected by local residents via a public competition and the beautifully designed homes were developed in collaboration with the local community, incorporating their hopes and concerns and addressing key issues including security and the design of green spaces. This process resulted in a successful Planning Application, bolstered by 107 letters of support from the local community.

So what will it take to make a project like one of these happen in Oxford?

To start with there are six very real and significant barriers that need overcoming in order to unlock small urban development sites: market fluctuations, complexities of land ownership, a lack of trust by developers, physical barriers to a site, and poor supply chains can prevent patchwork development. If you’ve got experience in any of these or you just want more of the nerdy details then you might also be interested in watching the recording of a digital roundtable we hosted in November 2021 which brought together practitioners from Bristol and Oxford to share knowledge on unlocking tricky sites.

As we attempt to pave the road ahead for an approach like this to happen in Oxford, we’ve had a go at sketching how we think a project like this could look. We’re calling it ‘Find the Gap’ and It’s a plan for the development of permanent housing but also explores a more temporary and immediate fix to the problems we face right now. Take a look and tell us what you think. If you’re a land-owner, housing provider, or modular housing provider interested in helping us make this happen then we’d love to hear from you.

In addition to Find the Gap, we’re also working with the Oxfordshire Community Land Trust (OCLT) on a project in Blackbird Leys to prototype this sort of development. Almost one-third of Oxford’s garage sites are in Blackbird Leys and the area also has some of the highest vacancy rates for garages, alongside one of the highest needs for housing in the city. OCLT currently have a live survey asking for the opinions of people who live or work in Blackbird Leys on this issue.